The widespread reduction in economic activity is having an unprecedented impact on Viet Nam’s world of work. Health workers are at the frontline of the fight against the virus. While they render a priceless service to society by discharging their daily duties, their work places expose them to the constant possibility of contagion. Many workers who continue to go to work have faced a profound change in their working methods. Enterprises have altered their working modalities to protect the health of workers, with a possible impact on output. Millions of workers are directly affected by the containment measures applied by the Government of Viet Nam. The widespread quarantine policy pursued by the Government has led to 14-day closures of many businesses or parts of businesses of all sizes and sectors. Social distancing in March and lockdown in March and April are resulting in a dramatic fall in revenues and workplace closures for workers employed in non-essential businesses.

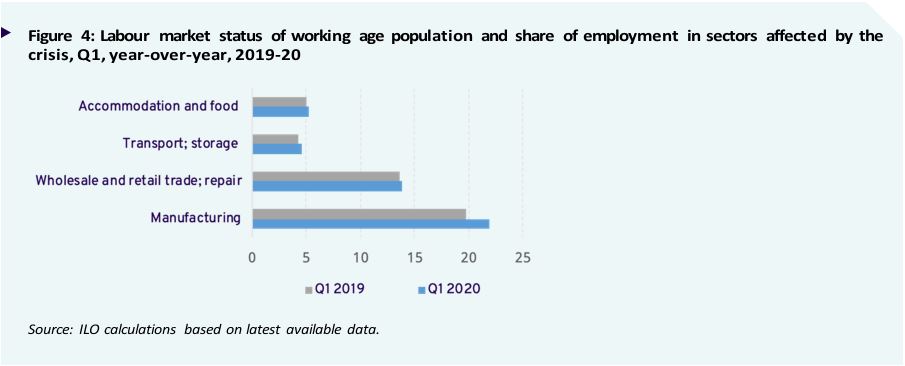

Factories serving the domestic market are reducing the working hours of employees, offering lowered wages or suspending production altogether and letting workers go. Workers in exporting enterprises are also subject to drastic reductions in working hours, contract suspensions, wage cuts and layoffs. A recent assessment from Viet Nam’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI), run in 46 provinces and cities, found that more than 76 per cent of the surveyed enterprises had reduced employee working hours through a range of options, from flexible working hours to, ultimately, layoffs. The national data from the first quarter is expected to show little impact of the COVID-19 crisis on Viet Nam’s labour market. An analysis of labour market indicators derived from the most recent data available reveals that employment, unemployment and working hours in the first quarter 2020 remained unaffected by the crisis. We find stable employment figures also in the sectors that experienced either a slowdown in growth or a contraction in the first quarter in connection to the crisis.

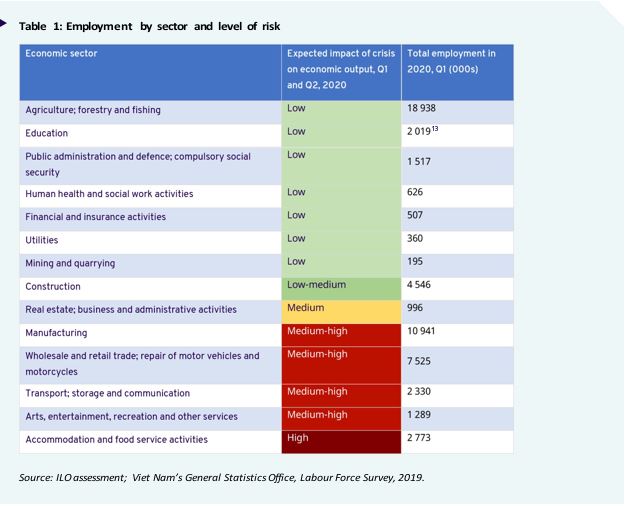

The share of tourism employment, a combination of several sub-sectors, in total employment remained stable too. Experience from past global crisis periods has shown that the labour market reacts to economic downturns with some delay, with enterprises first trying to maintain their workforces as long as possible through reduced production until this finally proves untenable. The current crisis is somewhat different though, in that containment measures affect employment directly, yet it is too early for the impact to show in the statistics. The latest round of labour force survey data collection by the General Statistics Office was completed over the first week of March. The strictest COVID-19 containment measures on travel, the partial lockdown and the closure of non-essential businesses were all applied from mid-March. Their full effect are expected to be adequately captured in the data from the second quarter. We can estimate the economic impact on economic sectors that are likely to bear the brunt of the crisis in the second quarter. Using economic data from the first quarter, as well as real-time information about containment measures and their consequences on enterprises and consumers, it is possible to estimate the reduction in economic output expected per sector over the first two quarters of 2020. Such reduction is influenced by the vulnerability of each sector to the direct effects of COVID-19 containment (as explained in section 2 of this note), or indirect ones, or both. Based on these consideration, we have assigned to each direct and/or indirect effect a level representing the expected severity of fall in economic output. Table 1 illustrates the results.

Based on the assessment illustrated in Table 1, around 25.8 million workers in Viet Nam are employed in sectors that are at risk to experience a significant (medium or high) reduction in economic output. The accommodation and food service sector as a whole is facing an especially devastating impact, with a severe contraction already visible in the first quarter. Economic activity in tourism (a combination of accommodation and food services, transport, as well as art and entertainment activities) has stopped. In addition, the hard-hit sectors include manufacturing. As discussed in section 2, industries involved in garment global supply chains, automotive assembly, and manufacturing of furniture are facing dramatic reductions in activity and widespread suspension of factory production due to cancellation of orders from national and international markets. Beyond the manufacturing sector, air transport, as part of the transport, storage and communication sector, has virtually come to a standstill, as has several activities in the areas of arts, entertainment and recreation.

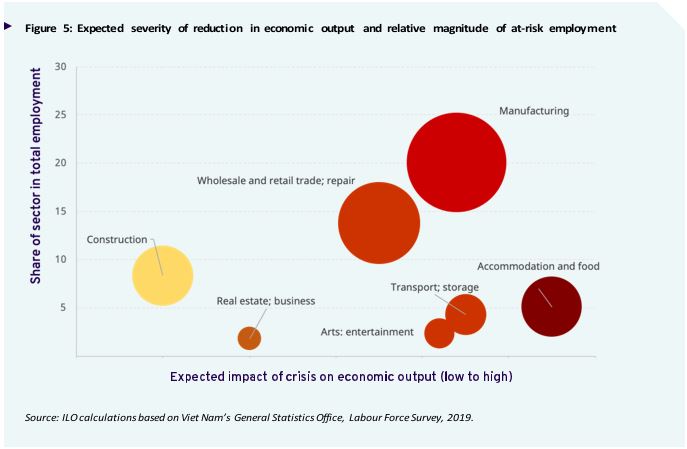

The employment impact of the crisis will depend on the level of economic disruption and the size of employment in each affected sector. Based on the assessment of reduction in economic output illustrated in Table 1, we can estimate the share of workers at risk of losing work either in its entirety or in terms of reduced hours or wages, or both. We envisage two scenarios: one lower-impact scenario in which containment measures are eased during the second quarter, and one higher-impact scenario where the measures remain largely in place. Figure 5 below shows the results of the exercise to identify the workers most at risk of job/livelihood loss in the face of the COVID-19 crisis.

The X-axis represents the economic impact, measured as a drop in economic output of each sector. The level of impact on each sector is assessed, on a scale from low to high, as summarized in Table 1. The Y-axis indicates the share in overall employment of each sector. The bubble size is the estimated number of workers at risk. Applying two scenarios, the ILO estimates that by the end of the second quarter the crisis can affect the livelihood of 4.6 to 10.3 million workers, whether through a decline in working hours, in wages or, ultimately, job loss. Based on the higher-impact scenario (see Annex I for further description of the methodology), this includes 3.8 million workers in manufacturing, 2.6 million workers in the wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles sector, and 1.4 million in accommodation and food service activities. The lower impact scenario, 1.8 million manufacturing workers will be at risk, as well as 0.9 million workers in wholesale and retail trade, and 0.9 in accommodation and food service activities. Agriculture, forestry and fishing, which overall employs 18.9 million workers, is considered a low-risk sector overall, but challenges may arise for subsectors working on export products.